An operational workflow is the repeatable sequence of steps your company uses to produce an outcome that matters: an invoice paid correctly, a customer issue resolved without drama, a new hire productive on day three instead of day thirty, a purchase approved without five inbox threads and a passive-aggressive “per my last email.”

That definition sounds polite. In practice, an operational workflow is a control system. It decides what happens next, who owns it, what information must exist before it can move, which rules apply, and what evidence is left behind when something goes wrong.

Most teams already have workflows. They just don’t have workflow management. They have habit. They have memory. They have Slack archaeology. And that’s why the same failures keep repeating with different timestamps.

Operational workflow vs process vs SOP

People use these terms interchangeably, then wonder why implementation turns into a mess.

A business process is the end-to-end “thing” the company does, from trigger to outcome. Customer onboarding is a process. Vendor payments are a process. Incident response is a process. Each process usually contains several operational workflows, because work rarely moves in one clean line without branching.

An operational workflow is the executable path inside that process. It’s the sequence of tasks and decisions that moves a case forward. It can be linear, conditional, multi-actor, partially automated, or heavily automated. What matters is that it has a start condition, a finish condition, and intermediate states that are meaningful enough to manage.

An SOP is documentation. It can be excellent documentation, and it can still be powerless. An SOP tells people what they should do. A workflow system makes it harder to do the wrong thing, and easier to do the right thing, even when everyone is tired and busy and slightly annoyed.

If your workflow collapses when one person is offline, it’s not a workflow. It’s a dependency with a name tag.

Why process management exists at all

Operational work fails in predictable ways. Requests arrive missing critical information. The wrong person picks it up. It sits in limbo because nobody knows who’s responsible. Someone does a workaround “just this once,” and the workaround becomes policy. Finally, finance asks why numbers don’t reconcile, and everybody stares at the ceiling like it’s a group therapy session.

Process management is how you stop treating those failures as personality problems. It turns them into system problems you can fix. The job is not to produce pretty diagrams. The job is to produce reliable outcomes with less time, less rework, fewer exceptions, and fewer “we can’t do anything until Mark replies.”

What an operational workflow is made of

Every operational workflow, whether it lives in a spreadsheet, a ticketing system, or a BPM tool, has the same underlying components.

There is always a trigger. Something initiates the workflow: a form submission, a customer email, a new order, a failed payment, an internal request, a release that broke production.

There are always states. A state is the truth of where the work is right now. “In review” is a state. “Blocked” is a state. “Waiting on customer” is a state. The state must be meaningful enough that a third party can look at it and know what is supposed to happen next.

There are always actors. Someone creates the case. Someone processes it. Someone approves it. Sometimes the actor is a system and the “task” is an API call.

There are always rules. Approval thresholds, mandatory fields, routing logic, compliance constraints, SLAs, escalation conditions. If rules are not explicit, the team will invent them live, inconsistently, with confidence.

There is always a definition of done. Without that, “done” becomes a social negotiation, which is the least efficient workflow engine ever created.

Types of operational workflows

If you don’t know the type you’re building, you’ll either over-engineer something simple or under-control something risky.

A linear workflow is the simplest pattern: Step A leads to Step B leads to Step C. Linear workflows are common in onboarding checklists and routine administrative tasks. Their weakness is that the real world introduces exceptions, and your “linear” workflow suddenly needs branching.

A conditional workflow includes decision points. If the request amount is above a threshold, it goes to a higher approver. If the customer is enterprise tier, the SLA changes. If the invoice fails a validation rule, it routes to exception handling. Conditional workflows are where process management starts paying for itself, because the cost of inconsistent decisions is high.

A multi-actor workflow includes handoffs. Multi-actor does not mean “more people.” It means ownership changes. Handoffs are where delay is born. They’re also where accountability disappears unless you deliberately design it back in.

A case-based workflow is less rigid. It’s used when each case has variations but still requires governance, auditability, and structure. Think investigations, compliance reviews, escalations, incident response. Case-based workflows need frameworks and templates, not rigid rails that force wrong steps.

An event-driven workflow is triggered and moved by events from systems. A payment settles, a subscription cancels, a deployment succeeds, a webhook fires. Event-driven workflows are powerful and dangerous. Powerful because they reduce manual work. Dangerous because they introduce duplicates, retries, partial failures, and the kind of “why did this fire twice” bugs that age teams quickly.

Workflow modeling that doesn’t waste time

You do not need complex modeling on day one. You need alignment. Then you need execution. Then you need refinement.

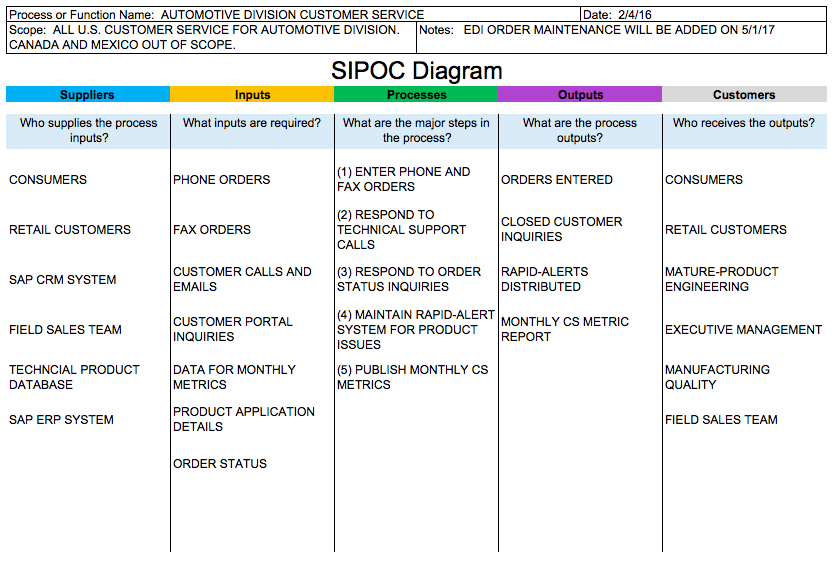

SIPOC is the fastest model for scoping. It forces clarity around suppliers, inputs, process, outputs, and customers. It’s not a diagram to impress anyone. It’s a sanity check to stop arguments like “who is the customer here” and “what does done actually produce.”

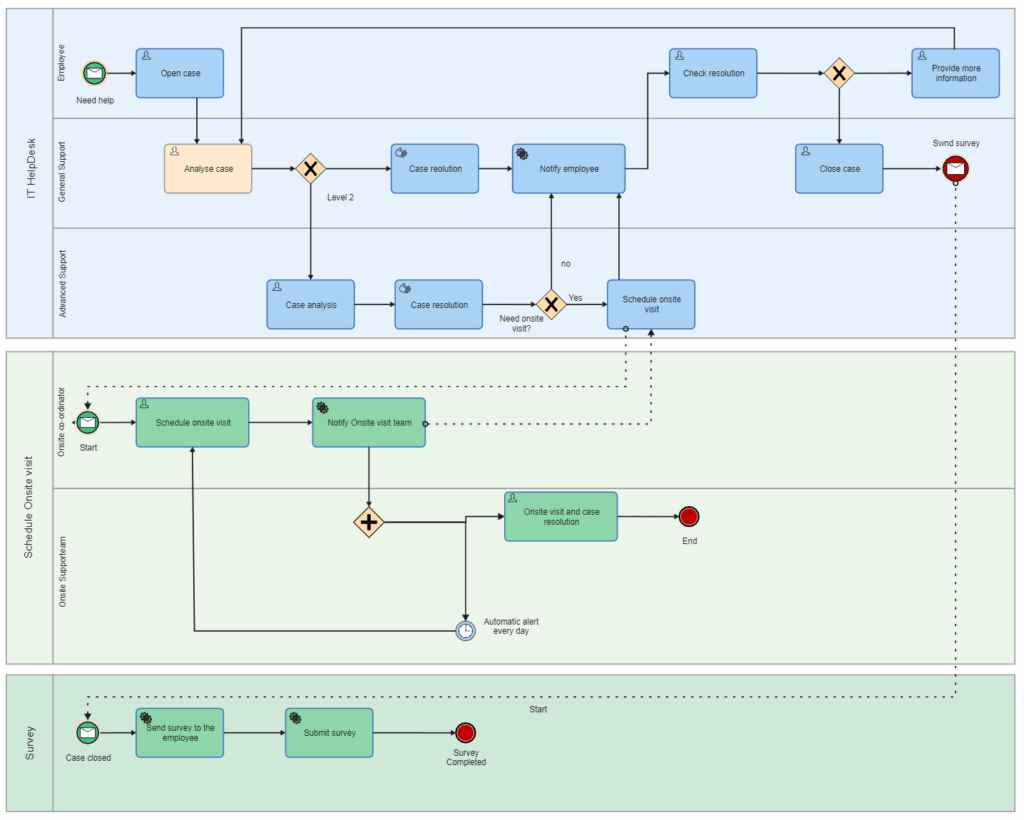

BPMN is useful when you have branching, multiple actors, approvals, escalation, and you want a model that translates into execution logic. BPMN is often avoided because it looks formal. The irony is that teams already have formal logic. They just execute it informally, inconsistently, and without records.

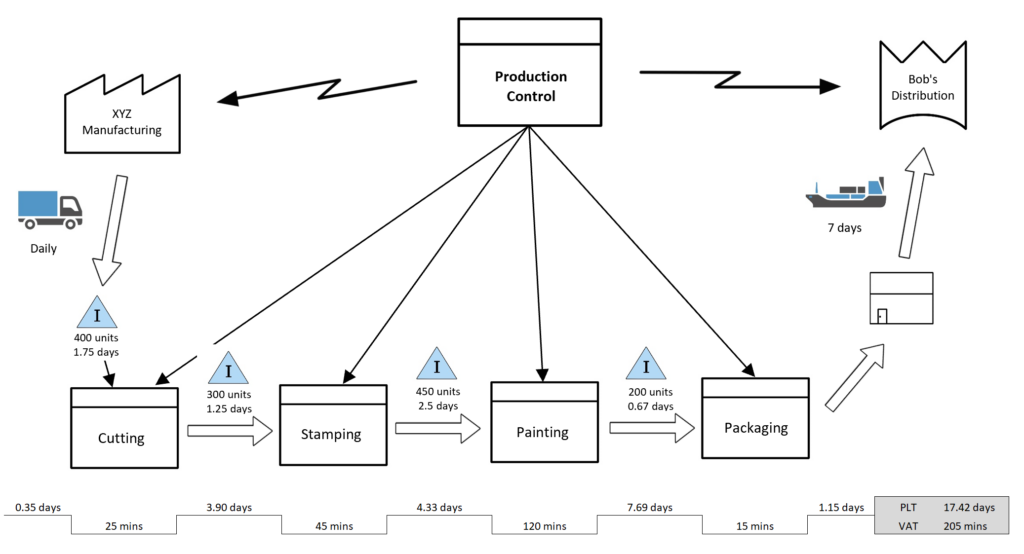

Value Stream Mapping is what you use when the workflow exists, but it’s slow and expensive. It separates active work time from waiting time. Most teams discover that waiting is the dominant activity in their process. That is not a moral failure. That is a design failure.

If you want to include visuals in the post, add a SIPOC table early, a swimlane diagram for one multi-actor example in the middle, and a simple value stream snapshot near the measurement section. Those three images cover the intent spectrum: definition, structure, optimization.

The operational workflow stack

A single tool rarely does everything well. Mature operations are a stack. Each layer has a job and a boundary.

Documentation and training live in a knowledge base. That’s where SOPs, decision rules, templates, and “how to handle exceptions” guidance should exist. Without this layer, your workflow tool becomes a place where tasks exist but context does not.

Intake lives in a form or structured entry point. Intake quality decides workflow quality. A workflow cannot run cleanly if it starts with garbage. If “missing info” becomes the default state, the real workflow is not “processing requests,” it’s “extracting basic details from people.”

Tracking lives in a task or ticket system. This is where states, ownership, due dates, and history exist. Tracking is the heartbeat. Without it, work becomes invisible.

Automation lives in an integration layer. This is where handoffs between tools stop relying on humans. Automation is not a luxury. It is how you prevent the slow rot of manual copy-paste processes that seem harmless until you scale.

Governance lives in approvals, permissions, audit trails, and decision policies. If governance is weak, your workflow can be fast but unreliable. If governance is too heavy, your workflow becomes a bureaucratic treadmill. The art is choosing where control matters.

Measurement lives in dashboards and metrics. If you can’t measure cycle time, throughput, backlog age, and SLA breaches, you can’t improve the system. You can only rearrange it and call it progress.

The four capabilities that separate real workflow management from “a board”

Operational workflow tools differ, but high-performing systems converge on four capabilities.

First is structured intake. The system forces the data required to run the workflow. It prevents work from entering the pipeline in an undefined state. It also reduces rework because missing data is handled at the point of creation, not discovered later when everyone is already context-switching.

Second is routing logic. The right work reaches the right person without negotiation. Routing can be based on category, region, product line, customer tier, severity, cost threshold, or current workload. The point is to stop the “anyone can grab it” model that creates inconsistent outcomes.

Third is approvals and auditability. Approvals are not about control for its own sake. They are about decision integrity. Audit trails prevent disputes because they record what happened, when, and why. If you cannot reconstruct decisions, you cannot manage risk. You can only hope.

Fourth is instrumentation. Cycle time and bottlenecks are not “nice to have.” They are the only way to know whether the system is improving or merely moving work around differently.

Efficiency is not speed. It’s throughput without rework.

Teams often optimize for speed. They shorten steps, skip approvals, and remove “friction.” Then errors increase, rework increases, and net throughput decreases. The workflow looks faster until you include the cost of corrections, escalations, refunds, churn, and internal resentment.

Good operational workflows reduce the total cost of completion. They minimize rework, minimize waiting, reduce ambiguity, and keep exception handling contained instead of leaking into every case.

Ten operational workflow examples, expanded and practical

The fastest way to understand operational workflows is to see them in the wild. Each example below includes what the workflow is really doing, what to automate, where governance belongs, and what measurements prove you improved it.

Example 1: Purchase approval workflow

A purchase approval workflow exists to control spend without turning managers into human bottlenecks. The trigger is a purchase request. The outcome is an approved purchase order with correct coding, or a clear denial with rationale.

In weak implementations, the request arrives via chat, missing vendor details, missing cost center, and missing urgency. The approver asks questions. The requester answers late. Finance gets surprised later. Everyone blames “communication.”

A strong purchase workflow starts with intake that forces the minimum viable data: what is being purchased, why it is needed, how much it costs, which cost center it belongs to, what vendor is involved, and when the purchase is required. Routing then applies thresholds. Small purchases can be approved quickly by a line manager. Larger purchases route to a higher approver, and compliance checks are applied automatically. If the request violates policy, it goes to an exception path instead of poisoning the main lane.

Automation should handle the boring parts: pre-filling vendor details, validating budget availability where possible, creating a purchase order record, notifying stakeholders. Governance belongs in thresholds and audit trails, not in endless meetings.

The metrics that matter tell you if control improved without killing velocity. Approval cycle time is obvious. Exception rate tells you whether policy and reality align. Spend visibility by category tells you whether the workflow is producing management intelligence or just approvals.

Example 2: Supplier invoice processing

Invoice processing is a workflow built to prevent three expensive outcomes: paying the wrong amount, paying the same invoice twice, and paying late because nobody could find the correct approver.

A weak invoice workflow is a shared inbox and a spreadsheet. The invoice arrives. Someone forwards it. Someone else “handles it.” Matching to purchase orders happens manually. Exceptions are handled ad hoc. Closing the books becomes an exercise in detective work.

A strong invoice workflow treats invoices as cases with a lifecycle. The invoice is captured, key fields extracted, and validation rules applied early. Matching to purchase orders and receipts should happen as close to automation as possible. Anything that fails matching is routed into a defined exception workflow with ownership and resolution steps, rather than being left to rot. Approvals should be explicit and tied to authorization rules, because “I assumed you approved it” is not a control mechanism.

Automation should do extraction, matching, duplicate detection, reminders, and posting to accounting systems when approved. Governance belongs in approval rules, vendor master control, and clear exception handling with audit trails.

Metrics include processing time, exception rate, duplicate detection rate, and late payment rate. If your exception rate is high, you don’t just have an invoice problem. You have an upstream purchasing problem.

Example 3: Expense reports

Expense reports are a perfect microcosm of operational workflow failure. The process is simple. The outcomes are emotionally charged. People hate it because it wastes time and feels like surveillance.

A weak expense workflow uses email threads, scanned receipts, and inconsistent approvals. People submit incomplete reports. Managers approve late. Finance chases people. Reimbursement delays become cultural poison.

A strong expense workflow makes it easy to do the right thing. It enforces required fields, categorization, and receipt quality at submission time. It applies policy rules automatically, flagging exceptions instead of forcing finance to manually police everything. Approvals are routed to the right manager. Reimbursements are triggered in a predictable cadence.

Automation handles policy checks, categorization, reminders, and posting to accounting systems. Governance belongs in clear rules and transparent exception handling, not in arbitrary financial judgment calls.

Metrics include time-to-reimburse, policy violation rate, and resubmission rate. If resubmission is high, the workflow is punishing users instead of guiding them.

Example 4: Employee onboarding

Onboarding is operational workflow with a multiplier effect. If you do it well, productivity rises, mistakes drop, and employee trust increases. If you do it badly, you pay for it for months.

A weak onboarding workflow is a checklist nobody owns. Accounts are created late. Access is wrong. Hardware is missing. New hires spend their first week feeling like an inconvenience.

A strong onboarding workflow starts before day one. The trigger is a signed offer with a start date. The workflow then provisions accounts, access, hardware, documentation, and introductions in a predictable sequence. The hiring manager has responsibilities, HR has responsibilities, IT has responsibilities, and the new hire is not forced to chase them.

Automation creates accounts, assigns groups, schedules standard meetings, generates tickets for hardware, and confirms completion. Governance belongs in access control and least privilege. Auditability matters because onboarding errors can become security incidents.

Metrics include time-to-first-commit for engineers, time-to-first-customer-response for support roles, and onboarding completeness by start date. If onboarding is repeatedly late, it’s not “busy season.” It’s missing ownership and triggers.

Example 5: Customer support triage and resolution

Support workflows exist to convert chaos into clarity. The trigger is an inbound request. The outcome is resolution, with the correct customer communication, internal documentation, and feedback loop into product.

Weak support workflows rely on heroic agents. They handle everything. Knowledge lives in their heads. When they leave, the workflow collapses.

Strong support workflows enforce triage. Each ticket gets categorized, prioritized, assigned, and tracked. Severity definitions are consistent. High-severity issues escalate with clear rules. Customer tier affects SLA. Ownership is explicit. Waiting states exist and are measurable.

Automation should handle routing, SLA timers, escalation notifications, and enrichment with customer context. Governance belongs in severity criteria, escalation policy, and audit logs.

Metrics include first response time, resolution time, reopen rate, escalation rate, and SLA breach rate. Reopen rate is a truth serum. It tells you whether you are resolving issues or merely closing tickets.

Example 6: Content operations workflow

Content operations is an operational workflow disguised as creativity. It fails when it becomes a freeform art project. It wins when it becomes a controlled system with room for good writing.

Weak content workflows start with “write about X.” No intent definition. No target reader. No acceptance criteria. Publishing becomes random. Updates never happen. The blog becomes a museum of outdated opinions.

Strong content workflows begin with a brief that forces clarity. The brief defines intent, angle, target audience, and what “done” means. Writing follows. Editing follows. Fact validation follows. On-page checks follow. Then publication. Then measurement. Then scheduled refresh. Most blogs skip the last two and wonder why traffic decays.

Automation can create tasks from a brief template, assign reviewers, push deadlines to calendars, trigger internal link checks, and schedule refresh cycles. Governance belongs in the definition of done and the review gate, especially for anything that could be wrong in a way that damages trust.

Metrics include brief-to-publish cycle time, update cadence compliance, and the percentage of posts with clean internal link structure. Content operations is where process management meets brand integrity.

Example 7: Lead qualification to sales handoff

Sales handoffs are workflows built to prevent expensive waste: ignoring good leads and chasing bad ones.

Weak workflows are “someone fills a form and maybe someone calls them.” Leads decay. Response time increases. Attribution gets messy. Sales complains about quality. Marketing complains about follow-up.

Strong workflows treat lead handling like an SLA-driven process. The lead is captured with sufficient context. Enrichment adds firmographic data. Scoring determines priority. Routing assigns the lead to the correct owner. Acceptance and follow-up have time expectations. Rejections require a reason, which becomes feedback into targeting.

Automation should do enrichment, scoring, routing, and reminders. Governance belongs in qualification criteria and acceptance SLAs.

Metrics include response time, acceptance rate, conversion rate to opportunity, and disqualification reasons. If disqualification reasons are vague, the workflow isn’t learning.

Example 8: Incident response workflow

Incident response is a workflow that must function under stress. The trigger is an incident. The outcome is mitigation, restoration, customer communication, and a postmortem that produces actual change rather than performative regret.

Weak incident workflows depend on whoever is awake. Communication is chaotic. Ownership is unclear. Timelines are reconstructed later with guesswork.

Strong incident workflows assign an incident commander, define severity, create a communication cadence, and separate mitigation from analysis. Work is tracked. Decisions are logged. Stakeholders are updated predictably. After resolution, the workflow continues into postmortem and remediation tasks with owners and deadlines.

Automation creates incident channels, pages on-call, attaches relevant dashboards, and logs events. Governance belongs in severity ladders, comms requirements, and postmortem enforcement.

Metrics include time to acknowledge, time to mitigate, time to recover, recurrence rate, and postmortem completion rate. If recurrence is high, the workflow is solving symptoms, not causes.

Example 9: Change management workflow

Change management exists because change is the biggest source of unplanned downtime. The goal is not to slow change. The goal is to make it safe.

Weak change workflows either don’t exist or exist as a bureaucratic ritual that teams bypass. High-risk changes ship without review. Low-risk changes get stuck in approvals. Everyone hates it, and then production breaks.

Strong change workflows differentiate by risk. Low-risk changes flow quickly with lightweight checks. High-risk changes require explicit review, rollback plans, and stakeholder communication. Scheduling and batching decisions are part of the workflow, not last-minute chaos.

Automation can attach impacted systems, enforce rollback plan fields, collect approvals, and generate release notes. Governance belongs in risk classification and approval rules.

Metrics include change lead time, change failure rate, rollback frequency, and unplanned work due to incidents triggered by change.

Example 10: Administrative request workflow

Administrative requests look simple until volume grows. Then they become a drain because they interrupt everyone and nobody owns the queue.

Weak admin workflows are emails and messages. Requests are duplicated. Status is unknown. People “follow up” repeatedly, which creates even more work.

Strong admin workflows centralize intake, categorize requests, route ownership, and expose status. They handle completion confirmation in a predictable way, including auto-close rules to avoid endless open loops.

Automation routes by category, sets SLA timers, sends reminders, and closes requests when confirmed. Governance belongs in intake standards and escalation rules.

Metrics include backlog size, age of oldest request, SLA breach rate, and category distribution. Category distribution often reveals what the company is failing to productize internally.

A method to design and implement operational workflows that don’t collapse

Step 1 is to map reality. This is the uncomfortable part, because it reveals where work actually happens. You collect the trigger, the end condition, the actors, the systems involved, the handoffs, the exceptions, and the current failure points. You don’t ask how it should work. You ask how it works when everyone is rushed.

Step 2 is to build a minimal executable version. You start with the happy path and make it run end-to-end. Intake, states, routing, and basic notifications. You resist the urge to model every exception. Exceptions get captured and triaged later, because building the perfect workflow before you have operational data is a Tell Me You’ve Never Operated This Without Telling Me move.

Step 3 is to add controls and automation where it pays. You automate repetitive actions that waste time and create errors. You introduce approval gates where mistakes are expensive. You define exception handling paths so exceptions don’t leak into the main flow.

Step 4 is to instrument and iterate. You pick a small set of metrics, watch them weekly, and make one change at a time. If you change ten things at once, you won’t know what worked. You’ll just have new problems and a new set of opinions.

Measurement that actually proves improvement

Cycle time measures how long it takes for a case to move from start to done. It reveals delay, not effort. Throughput measures how many cases you complete per period. It reveals capacity. Work in progress reveals how much work is currently in flight. It reveals overload. SLA breach rate reveals whether your operational promises are being met. Rework rate reveals whether work is being done correctly the first time.

Most teams discover that improving workflow efficiency is less about working faster and more about reducing waiting, reducing handoff friction, and reducing rework caused by missing information.

Automation ideas that make workflows feel “magical” without becoming fragile

Automation is not just notifications. Automation can create structure. It can enrich incomplete cases. It can enforce business rules. It can route work without negotiation. It can synchronize systems so you stop maintaining the same truth in three places.

If you add automation, you also inherit failure modes. Retries can cause duplicates. Events can arrive out of order. Systems can partially fail. That’s why idempotency matters. A workflow automation should be safe to run twice without creating two invoices, two tickets, or two approvals. This is where many “no-code automation” builds become expensive later: they optimize for building fast, not for being correct under failure.

Common mistakes that make workflow management worse

One mistake is designing workflows without a definition of done. This causes endless reopen cycles and “is it really finished?” debates.

Another mistake is creating too many statuses. People stop updating statuses when the system becomes a taxonomy exercise. Keep statuses meaningful. If a status doesn’t change behavior, it doesn’t deserve to exist.

A third mistake is allowing exceptions to live outside the system. The moment exceptions are handled in private messages, the system becomes fake. Your “workflow tool” becomes a ceremonial board while real work happens elsewhere.

Another mistake is failing to assign ownership at every stage. Work that is “owned by everyone” is owned by nobody. It rots quietly.

The last common mistake is not measuring anything. Without metrics, process management becomes theater. Meetings become louder. Improvements become cosmetic.